The Lure of Venice

by Jonathan Thomson

Like innumerable foreign artists before him, Vietnamese painter Pham Luan found Venice an enchanting place. His most recent series of paintings are a vibrant reminder of the truly evocative beauty of the city that draws artists and tourists alike to its environs continuously.

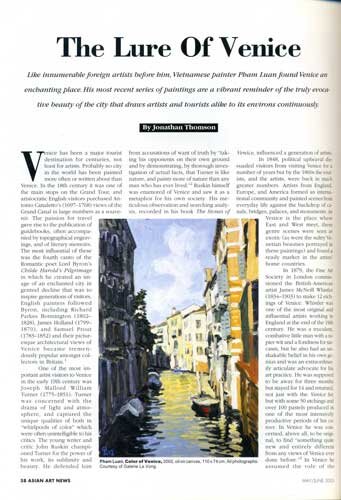

Colour of Venice. 2002

Venice has been a major tourist destination for centuries, not least for artists. Probably no city in the world has been painted more often or written about than Venice. In the 18th century it was one of the main stops on the Grand Tour, and aristocratic English visitors purchased Antonio Canaletto’s (1697-1768) views of the Grand Canal in large numbers as a souvenir. The passion for travel gave rise to the publication of guidebooks, often accompanied by topographical engravings, and of literary memoirs. The most influential of these was the forth canto of the Romantic poet Lord Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage in which he created an image of an enchanted city in genteel decline that was to inspire generations of visitors. English painters followed Byron, including Richard Parkes Bonnington (1802-1828), James Holland (1799-1870), and Samuel Prout (1783-1852) and their picturesque architectural views of Venice became tremendously popular amongst collectors in Britain.1

One of the most important artist visitors to Venice in the early 19th century was Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775-1851). Turner was concerned with the drama of light and atmosphere, and captured the unique qualities of both in “whirlpools of color” which were often unintelligible to his critics. The young writer and critic John Ruskin championed Turner for the power of his work, its sublimity and beauty. He defended him from accusation of want of truth by “taking his opponents on their own ground and by demonstrating, by thorough investigation of actual facts, that Turner is like nature, and paints more of nature than any man who has ever lived.”2 Ruskin himself was enamored of Venice and saw it as a metaphor for his own society. His meticulous observation and searching analysis, recorded in his book The Stones of Venice, influenced a generation of artists.

In 1848, political upheaval dissuaded visitors from visiting Venice for a number of years but by the 1860s the tourists, and the artists, were back in much greater numbers. Artists from England, Europe, and America formed an international community and painted scenes from everyday life against the backdrop of canals, bridges, palaces, and monuments. As Venice is the place where East and West meet, these genre scenes were seen as exotic (as were the sultry Venetian beauties portrayed in these paintings) and found a ready market in the artists’ home countries.

In 1879, the Fine Art Society in London commissioned the British-American artist James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) to make 12 etchings of Venice. Whistler was one of the most original and influential artists working in England at the end of the 19th century. He was a truculent, combative little man with a rapier wit and a fondness for sarcasm, but he also had an unshakable belief in his own genius and was an extraordinarily articulate advocate for his art practice. He was supposed to be away for three months by stayed for 14 and returned, not just with the Venice Set, but with some 50 etchings and over 100 pastels produced in one of the most intensively productive periods of his career. In Venice he was concerned, above all, to be original, to find “something quite new and entirely different from any views of Venice ever done before.”3 In Venice he assumed the role of the flâneur and observed and drew with exquisite tenderness the myriad details of the by-ways and backwaters of the city and the evanescent atmosphere that envelops it all.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries the color and light of Venice came to inspire another generation of artists familiar with contemporary developments in European painting. For many of them their common concern was the color of light. In 1888, the critic Bernard Berenson wrote: “one soon forgets to think of form here, going almost mad on color, thinking in color, talking color, almost living on color. And for one that enjoys color this certainly is paradise.”4 The list of artists who visited Venice at this time – from France, Britain, America, Australia, and elsewhere – is legion.

This potted history is by way of contextualizing some of the issues that artists have grappled with and continue to do so when dealing with the unique and timeless beauty of Venice. One of the more recent converts to the beauty of Venice is the Vietnamese artist Pham Luan. In his first series of works painted outside of Vietnam, Luan has captured the ability of this city to astound and to enchant, to dazzle and to seduce.

He visited Venice twice in 2002, in June and October, for just three days at a time. He made some small paintings based on the impressions he received during his first visit in June. He was pleased with their reception when he showed them to friends in Hanoi and was encouraged by his Hong Kong dealers to return in October, to sketch and to take photographs, to try to fix the city in his memory so that on his return to Hanoi he could paint the city, not because it is “exotic” (for most Western audiences it is Hanoi that is exotic) but specifically because it is so well-known as a subject for art.

Of all the artists who had visited Venice before him, Luan names just one – Monet. Monet visited Venice only once, in 1908, when he was feeling discouraged with the progress of his work on his great water-lily series. According to his biographer Virginia Spate: “he intended to paint only a few canvases ‘to preserve its souvenir’, but was soon ‘ravished’ by it, once again ‘possessed by work’, obsessed by this unique light and regretful that he had not come to Venice when he was younger and ‘dared everything!”5 Like Monet, Luan was captivated by the quality of the light in Venice. He was surprised at its brightness and clarity, and enchanted by the way it plays on the water. Above all, he was struck by the color in the shadows – “even in the shadows I see light.”

Luan is first and foremost a landscape painter. In most of the paintings in this series he ignores the crowds of people that throng the city throughout the year and paints the play of light on the buildings and waterways as if they are natural features. Where figures do appear, they are treated summarily, as dabs and daubs or pure color. He is concerned to capture the character of the city in many different moods. He walked the streets from dawn to dark, taking photographs and making sketches, often returning to the same vantage paint at different times of day in order to record the look and feel of the city in different circumstances.

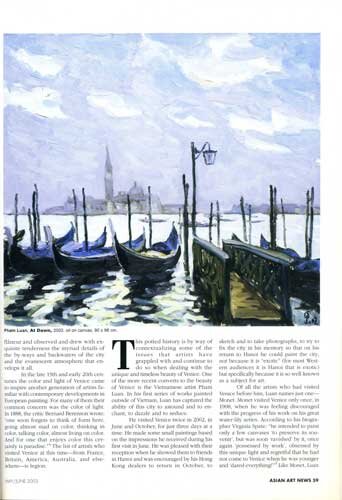

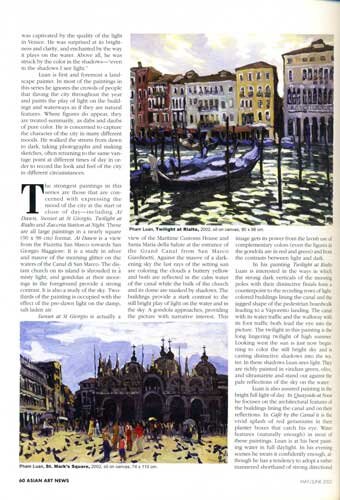

The strongest paintings in this series are those that are concerned with expressing the mood of the city at the start or close of day – including At Dawn, Sunset at St Giorgio, Twilight at Rialto and Zaccaria Station at Night. These are all large paintings in a nearly square (90 x 98 cm) format. At Dawn is a view from the Piazetta San Marco towards San Giorgio Maggiore. It is a study in silver and mauve of the morning glitter on the waters of the Canal di San Marco. The distant church on its island is shrouded in a misty light, and gondolas at their moorings in the foreground provide a strong contrast. It is also a study of the sky. Two-thirds of the paintings is occupied with the effect of the pre-dawn light on the damp, salt-laden air.

Sunset at St Giorgio is actually a view of the Maritime Customs House and Santa Maria della Salute at the entrance of the Grand Canal from San Marco Giardinetti. Against the mauve of a darkening sky the last rays of the setting sun are coloring the clouds a buttery yellow and both are reflected in the clam water of the canal white the bulk of the church and its dome are masked by shadows. The buildings provide a stark contrast to the still bright play of light on the water and in the sky. A gondola approaches, providing the picture with narrative interest. This image gets its power from the lavish use of complementary colors (even the figures in the gondola are in red and green) and from the contrasts between light and dark.

In his painting Twilight at Rialto Luan is interested in the ways in which the strong dark verticals of the mooring poles with their distinctive finials form a counterpoint to the receding rows of light-colored buildings lining the canal and the jagged shape of the pedestrian boardwalk leading to a Vaporetto landing. The canal with its water traffic and the walkway with its foot traffic both lead the eye into the picture. The twilight in this painting is the long lingering twilight of high summer. Looking west the sun is just now beginning to color the still bright sky and is casting distinctive shadows into the water. In these shadows Luan sees light. They are richly painted in viridian green, olive, and ultramarine and stand out against the pale reflections of the sky on the water.

Luan is also assured painting in the bright full light of day. In Quayside at Noon he focuses on the architectural features of the buildings lining the canal and on their reflections. In Café by the Canal it is the vivid splash of red geraniums in their planter boxes that catch his eye. Water features (naturally enough) in most of these paintings. Luan is at his best painting water in full daylight. In his evening scenes he treats it confidently enough, although he has a tendency to adopt a rather mannered shorthand of strong directional brush marks and a more limited palette which make the picture plane appear shallower than perhaps he intends. Notwithstanding, his use of robust impasto effects helps to emphasize the patterned surface of the picture.

Luan paints quickly. Before he starts each painting, he takes his time reviewing his sketches and looking at a great many photographs as an aide – mémoire to what he saw and felt when he was in front of the motif. Once he has the image fixed in his mind’s eye, he sets to work, taking three to four days to complete each painting. He uses a thick creamy paint and quite large brushes. He applies his paint quickly and confidently in an exuberant impasto and rarely is there any evidence of hesitation or of having reworked any part of the image. He uses pure saturated colors; when he does mix his colors on the palette, he never overworks them and the resulting mixtures reflect a greater sense of light. In this way he is able to achieve brilliant luminous effects despite using surprisingly few colors in each work.

This series of paintings indicate that Luan was quite happy in the role of a conventional tourist in Venice. He was content to paint the famous panoramas, grand buildings and scenes observed from the well-worn track between the Piazza San Marco and the Rialto. He does not indicate any interest in losing himself in the labyrinthine alleys and backwaters or in recording the intimate details so tenderly captured by both Ruskin and Whistler. He takes Venice as his subject and records its beauty in his established style and the results are strong, confident paintings with exuberant color and contrast. But was he moved by Venice? One smaller painting suggests that he was. A Glorious Afternoon is a view of a stretch of the Grand Canal but in this case the subject is not the feature of the work. It is a study of the play of light on water. It is painted with Luan’s customary confidence and bravura in high-keyed color but it is more close-toned and employs fewer contrasts than his other works. It is descriptive and decorative but more atmospheric and evocative than his other work. In this work he has captured not just the look, but also the heart of the city.

Notes:

1. Reitlinger, Gerald The Economics of Taste: The rise and fall of the picture market 1760 – 1960, Holt Rinehart and Winston, New York, 1964

2. Ruskin, John Modern Painters Volume 1, George Allen, London, 1904, Preface to the 2nd Edition p.xlix

3. Whistler to Charlie Hanson, postmark Venezia/ 2-5-90, GUL H55, cited in Grieve, Alistair Whistler’s Venice, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2000, p.181

4. Hirshler, Erica “Gondola Days: American Painters in Venice” in Stebbins, Theodore E Jr. The Lure of Italy: American Artist and the Italian Experience 1740-1940, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1992 p.123

5. Spate, Virginia The Color of Time: Claude Monet, Thames and Hudson, London, 1992, p. 263