Painting The Town

by Ian Findlay

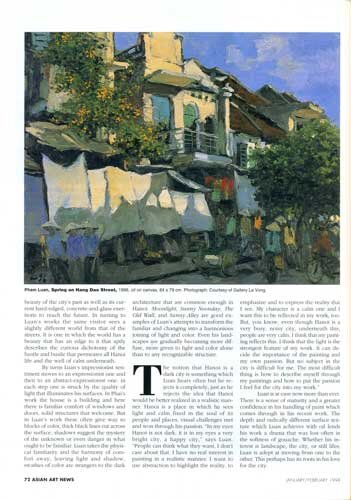

Sunny Alley. 1997

For generations of modern and contemporary Vietnamese painter, Hanoi has been a fascinating city of visual magic. Among the older generation of artists such as Bui Xuan Phai (1921-1988), Nguyen Sang (1923-1988), and Nguyen Tu Nghiem (b.1922) the city’s history, architecture, people, lakes, and streets came alive on their many canvases and drawings leaving a wonderful legacy of time and place. Through war and revolution the face of Hanoi changed slowly until the Vietnamese government began to open up the world (doi moi) in the late 1980s. But then, for the most part, the old artists who had studied under the French at the celebrated Ecole des Beaux Art de l’Indochine de Hanoi had either died or put away their brushes.

Over the past seven years, however, the changes to Hanoi’s streets and skyline have been many and varied. There are times when it would seem that the anarchy of street capitalism with its cellular phones, shiny new motorcycles, rock music, and startled tourists, has destroyed all of the city’s former tranquility and romance. Reality, however, is a bit of both. Hanoi’s past remains, but not entirely the one that had inspired older artists. The past is present in the buildings, the dress, the energy of the people, and the narrow streets and pleasant boulevards, but now it is being tempered by a modern hand. Recording the city’s changing life and times is a younger generation of artists such as Pham Quang Ving, Le Quang Ha, Pham Luan, and Nguyen Than Chuong. Each has their own distinct style and favorite medium, but only Pham Luan has chosen Hanoi as his exclusive subject for all his art.

A self-taught painter with a singularly forceful commitment to art, Pham Luan, 43, is gradually taking his place at the forefront of the new generation of Hanoi painters as well as an assured place among the finest of those who dedicated themselves to recording the city. Hanoi offers the artist exhaustive pictorial postures and Luan has sifted them to paint with growing confidence. Luan’s work can be divided into three groups: landscape, cityscape, and still lifes, although he has occasionally painted portraits.

The physical geography of old Hanoi still lends itself to interpretations that would be recognizable to an earlier generation. Over the past ten years, with the burgeoning interest in modern and contemporary Vietnamese art, many artists have tried to imitate the late Bui Xuan Phai’s best work. Phai was the Utrillo of Hanoi and not to be imitated. The line, color, tone, form, perspective, and pictorial structure of his work have captured the imagination and the brush of many artists seeking to emulate the old master’s style. The results are disappointing. What is lacking in the vast majority of pretenders’ works is the compelling draughtsmanship, the insights of time and place, the enigmatic quality of his architecture, the defiant poverty and mystery of his streets.

Where Phai’s work has bothuthe enchantment and the melancholy of dreams, even his abstract works (not surprising given his life and times), Pham Luan’s work is a celebration of light, with rarely a hint of sadness. It is not that Luan is painting to please a particular audience, one whose expectations are for works that reflect only a positive view of the world. Luan paints for himself from the uninhibited love he feels for the city in which he was born and grew up. Indeed, today he lives and paints in the house in which he was born on Phu Dong Thien Vuong. His is the independent way, uninfluenced by others, though he does nod in Phai’s direction with respect.

“No other Vietnamese artists have been important to me, really, and none has influenced me,” says Luan. “I respect Bui Xuan Phai who always painted the city but I don’t really know much about the older painters. I do think that my work is different in that I have a particular point of view about the sunlight of the city. I am very moved when I paint the city I love. I feel strongly rooted to this city. The house in which I live gives continuity to my life. It is like a living person to me.”

If one sees the influence of the French painter Albert Marquet (1875-1947) in the work of Phai, it is the influence of Claude Monet (1840-1926) and the Impressionists that one sees to some extent in Luan’s work. One might even consider Turner here as an influence on Luan. Pictorial presentation aside, Luan derives his subtle understanding of atmosphere, the effects of light at different times of the day (and night), the power of shadow, and the potency of environment from the Impressionists. These are things that suit Luan’s voyage of discovery of Hanoi, from its Old Quarter to its changing modern skyline. That Luan holds fast to these notions, while other artists of his generation reject them, from such a distant past and a very different culture gives one some idea of Luan’s determined individuality, his romantic notions of Hanoi, and his understanding of the changes he sees in the city. The critic Thai Ba van described the city, in reference to Luan’s own world, as possessed “Like a person’s life, Hanoi has the grey, sad beauty of slow afternoons, and the beauty of sunlight when dawn is approaching.”

“I see great changes in the city,” says Luan, who has sketched it regularly over the past 25 years, and which now serves as a repository from which he selects items to refresh his memory when painting. “The flower markets on the street used to be so few, now there are many. Around Truc Bach Lake the skyline behind the traditional houses are changing. The skyline is being filled with tall buildings. This doesn’t bother me as a painter since I have many sketches and I can draw on them to maintain traditions and views of the changing city. My sketches are like a diary for me now. The sketches are old reflections of the past, but the paintings are of my passion.

“I still sketch. I like sketching because it is important to me. When I joined the army, I began to sketch, mush in the same way a lot of artists of my generation, in their thirties and forties, did during their military service and who also began to make art in the military. I sketch as a point of reference for when I am painting. But the end product is very different.”

The ink sketches on paper from the early 1970s and 1980s are brief impressionistic works done more to capture the atmosphere than physical accuracy of place and structure. This is something which has carried over in all his work, whether his subjects are the apricot flowers of spring, a flower farm, café life, the white milk flowers of winter, the fire flowers of May, groups of people at the flower stalls, houses, streets, landscapes, still lifes, and alleys. Whether Luan uses gouache or oil, as in Sunny Day (1997), Rainy Day (1997), Sunny Noonday (1997), Moonlight (1997), The Old Wall (1997), and Sunny Alley (1997) his search for a strong surface texture, boldness of line, and quest for the right light with which to describe the environment and his emotion is a constant. A visitor walking Hanoi’s streets is unfailingly aware of the toughness and the beauty of the city’s past as well as its current hard-edged, concrete-and-glass exertions to reach the future. In turning to Luan’s works the same visitor sees a slightly different world from that of the streets. It is one in which the world has a beauty that has an edge to it that aptly describes the curious dichotomy of the hustle and bustle that permeates all Hanoi life and the well of calm underneath.

By turns Luan’s impressionist sentiment moves to an expressionist one and then to an abstract-expressionist one: in each step one is struck by the quality of light that illuminates his surfaces. In Phai’s work the house is a building and here there is familiar comfort of windows and doors, solid structures that welcome. But in Luan’s work these often give way to blocks of color, thick black lines cut across the surface, shadows suggest the mystery of the unknown or even danger in what ought to be familiar. Luan takes the physical familiarity and the harmony of comfort away, leaving light and shadow, swathes of color are strangers to the dark architecture that are common enough in Hanoi. Moonlight, Sunny Noonday, The Old Wall, and Sunny Alley are good examples of Luan’s attempts to transform the familiar and changing into a harmonious joining of light and color. Even his landscapes are gradually becoming more diffuse, more given to light and color alone than to any recognizable structure.

The notion that Hanoi is a dark city is something which Luan hears often but he rejects it completely, just as he rejects the idea that Hanoi would be better realized in a realistic manner. Hanoi is a place in which he sees light and calm fixed in the soul of its people and places, visual challenges met and won through his passion. “In my eyes Hanoi is not dark, it is in my eyes a very bright city, a happy city,” says Luan. “People can think what they want, I don’t care about that. I have no real interest in painting in a realistic manner. I want to use abstraction to highlight the reality, to emphasize and to express the reality that I see. My character is a calm one and I want this to be reflected in my work, too. But, you know, even though Hanoi is a very busy, noisy city, underneath this, people are very calm. I think that my painting reflects this. I think that the light is the strongest feature of my work. It can decide the importance of the painting and my own passion. But no subject in the city is difficult for me. The most difficult thing is how to describe myself through my paintings and how to put the passion I feel for the city into my work.”

Luan is at ease now more than ever. There is a sense of maturity and a greater confidence in his handling of paint which comes through in his recent work. The depth and radically different surface texture which Luan achieves with oil lends his work a drama that was lost often in the softness of gouache. Whether his interest is landscape, the city or still lifes, Luan is adept at moving from one to the other. This perhaps has its roots in his love for the city.

“I specialize in painting the landscape of the streets in Hanoi. I always paint Hanoi so there is no difficulty in moving from one to the other. I paint the old town of Hanoi, but for me there is nothing different from the landscape of that to a flower farm because what I paint is the heart of Hanoi,” he says. “Hanoi is made up of many lakes and small parks and villages so that they offer me in equal measure of landscape, cityscape, and still life. These are bound together in the city I see. The landscape of the city and the old town are the same for me, parts of the whole. Every corner of the city is special for me. The main thing that I want to say in my work is about the sunlight which comes through the trees and onto the lakes, the sunlight in the morning, the afternoon, and in the sad time of winter. When you see and understand this, then you see and understand Hanoi.”

Luan, born in Hanoi in 1954, has made a world that is grand through broad brushstrokes and attention to light. And though he is not always successful – his figures and still lifes sometimes seem hesitant – in capturing the spirit of the place as he would like, he does not shirk from the challenge. He sketches and paints with utter disregard to the fashions of the day; and there are many in Vietnam as painters compete in the lucrative commercial market. A criticism by many critics from the West is that contemporary Vietnamese painting does not reflect the conflicts of current society and that his work is conservative and not progressive enough in this day of greater freedom in Vietnam. He rejects these criticisms without the slightest regret. It is painting his own vision that is most important.

“I want to be optimistic to others. I don’t want to paint about the evils of society. I want to bring joy. This is why I paint what I paint. And I do paint a lot. I feel that everyday I have to paint or to sketch. If I don’t paint, it doesn’t mean I feel sad. But when I satisfied with a work, I am happy. And I feel refreshed when I can do something better the next day,” he says. “My thinking is that before painting I have to look at the sketches that I have done and choose the sketch I like and move on from there. I always use oil on canvas or gouache on paper but never acrylic. The time it takes to do a painting depends on the work. It can take many months to finish a work. This is because I may have a sketch that is difficult to make it into a painting. But I feel that I have changed a lot in my way of painting. My brush work is stronger than before. The topic hasn’t changed but my way of seeing and thinking have changed. And I am always looking for a new ways to express myself in my work.”

“Pham Luan makes new footprints on an old path – a path young painters in Vietnam do not want to tread….” writes the critic Phan Cam Thuong in a new book on Pham Luan. These “new footprints” have been helped by Luan’s ability to travel, to see first-hand that which he saw before only in books, and to speak with others whose painting “voices” are very different from his own. All of these experiences may well help to change the course of his art in the future, but for now he sees his work as Vietnamese, with its own unique voice which does reflect the Vietnamese spirit and culture of today.

“The fact that Vietnamese people buy my work suggests that my work reflects this spirit. But why, is difficult to explain,” he says. “I can only do the work that is my own, and being a Vietnamese the spirit is there in my work.”